The local Gordian’s Knot Association was incorporated in 1934. Officers were C. Hector Harmon, president; W. Alexander Wilson, vice president; L. Benjamin Andrews, critic; W. Sac-Bill Cummings, secretary; A. Lewis Smith, assistant secretary; E. Benjamin Cooper, treasurer; J. Colden Tubman, curator; E. Monroe Cummings, president emeritus; W. Alexander Tubman, president emeritus.

Members included S. David Cummings; R. Filmore Neal, S. Ashford Brewer, A. Lewis Weeks, A. Augustus Howard, W. E. Avey, A. Dash Wilson, Jr., and D. Eugene Lincoln, J. Horatio Thorne.

Footnote: Acts of the Liberian Legislature, 1934, p. 36.

Category: Uncategorized

Baptist manual school

The town was erected on unoccupied land that was separated from Bob Grey’s town by a hill. By the time Skinner sent his letter, Edina’s main street had been cleared and six lots deeded to citizens.

By April 1836, the Baptist missionaries had already asked for land on the hill to build a manual school that would serve the children of both Edina and the local ruler’s town. According to Skinner, Bob Gray was in favor of the school and had promised to send the children of his town.

Footnote: E. Skinner, “Liberia: Extracts of a letter,” African Repository, June 1836, p. 169.

Impact of slave trade

As a result of the slave trade, societies along the Windward Coast of West Africa went from supplying rice to European vessels to experiencing food shortages.

In 1818, the British Anti-Slavery Squadron began putting pressure on major slave trading areas like Rio Pongo, the Gallinas and Dahomey. As a result, the traffic moved to previously minor ports like Cape Mount and Cape Mesurado. The area around Cape Mount alone is said to have shipped around 3,000 persons in 1823 and about 15,000 per year between 1840 and 1850.

Footnote: Dan Morgan, Merchants of Grain (New York: Penguin, 1980), pp. 454-455, and Vernon R. Dorjahn and Barry L. Isaac, Essays on the Economic Anthropology of Liberia and Sierra Leone (Philadelphia: Institute for Liberian Studies, 1979), p. 21.

Highly productive farms

In 1850, a visitor described Caldwell as stretching about six miles along the river bank, with houses up to a quarter mile apart. Local farms were highly productive, in part due to the rich and moist riverbank soil. The town was already divided between Upper and Lower Caldwell.

In 1867, the local St. Peter’s Episcopal Church was noted as having been “kept open regularly and supplied with religious services.” St. Peter’s operated two outreach missions, one in New Georgia and Virginia. In 1881, the Methodist Episcopal Church of Lower Caldwell was incorporated. Named officials were Horatio B. Capehart (pastor), Isaac Lawrence (trustee), Francis T. Clark, Jr. (trustee), C.R. Sims (trustee), A.F. Travis (steward), Zeal Prichard (trustee) and James Bunyan (trustee).

Footnote: J. W. Lugenbeel, “Sketches of Liberia – No. 2,” African Repository, July 1850, p. 207; “Religious Services in Mesurado County, African Repository, Nov. 1867, p. 343; Acts of the Liberian Legislature, 1881, p. 11-12.

Arthington

Arthington is located on terrain that is hilly and uneven. It lies about two miles in from the St. Paul’s River and four miles northwest of Millsburg. [footnote]”Arthington, Liberia,” African Repository, Nov. 1873, p. 337.[/footnote]

The town is named in honor of Robert Arthington of Leeds, England, who funded the relocation of its founders from the southern United States. [footnote]”Arthington, Liberia,” African Repository, Nov. 1873, p. 337.[/footnote]

The site selected for Arthington was previously “impenetrable forest, six miles from any settlement.” According to Edward W. Blyden, the “only sounds to be heard were those made by birds on the tops of the lofty trees. There was no opening through the thick forest and dense undergrowth but the narrow path traveled for generations.” [footnote]”Visit to Arthington, African Repository, April 1889, p. 44.[/footnote]

The first group of 79 repatriates, led by Alonzo Hoggard, came from Windsor, North Carolina. In December 1869, they landed in Liberia. While the women and children stayed in Monrovia, the men began clearing the land in March 1870. [footnote]”Arthington, Liberia,” African Repository, Nov. 1873, p. 337; “Visit to Arthington, African Repository, April 1889, p. 44.[/footnote]

They had to contend “with the unbroken wilderness, make clearings and build their huts, eating the fare which, after dividing with their families, was left to them from the [American Colonization] Society’s rations.” [footnote]”Visit to Arthington, African Repository, April 1889, p. 44.[/footnote]

Like many repatriates from the U. S. after the Civil War, those who settled Arthington were dirt poor when they arrived. But, as noted by the New Era newspaper, they were “intelligent, active, industrious, and enterprising.” [footnote]”Arthington, Liberia,” African Repository, Nov. 1873, p. 337.[/footnote]

Three of their leaders were Alonzo Hoggard, Solomon York and Richard Rayner. Their progress was described by a visitor who arrived skeptical but left impressed.

Hoggard, for example, had “no assistance from native boys, no aid but four small sons, and with them alone he has planted out five thousand coffee trees and is cultivating one-and-a-half acres in potatoes, two acres in cassava, four acres in rice, one-half acre in eddies, besides many garden vegetables.” He also had eight hogs. [footnote]”Arthington, Liberia,” African Repository, Nov. 1873, p. 337.[/footnote]

Within three years, York had “nearly three thousand coffee trees growing, many bearing, and a large supply of cassavas, eddies, and other bread stuff.” Rayner, too, had planted a large lot of coffee. He also had “some acres of sugar-cane, some ginger, and his wife offers to sell a few barrels of Indian corn, the result of her own industry.” [footnote]”Arthington, Liberia,” African Repository, Nov. 1873, p. 337.[/footnote]

The first group was joined in 1871 by repatriates from Clayhill, South Carolina led by Jefferson Bracewell. The second group included Solomon Hill and June Moore, who together formed one of the country’s most prosperous trading companies. [footnote]”Arthington, Liberia,” African Repository, Nov. 1873, p. 337.[/footnote]

According to Edward W. Blyden, a frequent visitor to Arthington, some members of this second group knew the African ethnic groups to which they were connected. Hill was one. His mother was Gola, he said, and his father was from an ethnic group along the Niger. [footnote]”Visit to Arthington, African Repository, April 1889, p. 44.[/footnote]

With the aid of his seven sons, Bracewell cleared and planted thirty acres in one year. A visitor in 1873 noted, he had “1,100 coffee trees, made his large crops of rice, potatoes, and eddoes, so as to supply his own family; imported a sugar-mill, and made his own sugar and syrup last season. He has made a large coffee nursery, and is now tanning some of the best leather used in this country.” [footnote]”Arthington, Liberia,” African Repository, Nov. 1873, p. 337.[/footnote]

Bracewell had been so perpetually busy, a reporter for the New Era newspaper joked, he had no time to get sick. “His wife and daughter spin and weave all the cloth that he and those boys wear, and he has built with his own hands his own dwelling house, outside store-house, weaving and loom house for his wife, and a house for tanning.” [footnote]”Arthington, Liberia,” African Repository, Nov. 1873, p. 337.[/footnote]

Even more successful was Hill, a carpenter, cabinet maker, blacksmith, engineer and farmer who could neither read nor write. He arrived in 1871 with $30, all of which was spent to build his first temporary residence. By 1889, a visitor called him “probably the most independent man” in West Africa. [footnote]”Visit to Arthington, African Repository, April 1889, p. 44.[/footnote]Hill planted 180 acres of coffee alone, along side foodstuff.

In 1889, he had “more than fifty bags of coffee from last season, which he has been under no necessity to sell. It is now thoroughly cured and will command a high price. He will produce ten thousand pounds of coffee this season, besides other agricultural articles.” [footnote]”Visit to Arthington, African Repository, April 1889, p. 44.[/footnote]

Hill also built his own house, “a large two story frame building with verandah and attic, and outhouses …some covered (roof and sides) with corrugated iron.” [footnote]”Visit to Arthington, African Repository, April 1889, p. 44.[/footnote]

A visitor called the furniture Hill built “specimens of first-rate workmanship, and being made of native wood procured on his land, is far superior to anything of its kind he could import. His skill would command patronage in any city in the world.” [footnote]”Visit to Arthington, African Repository, April 1889, p. 44.[/footnote]

As a blacksmith, Hill made his own tools. “His lathe for turning wood and iron was constructed by himself in a very simple but effective style.” [footnote]”Visit to Arthington, African Repository, April 1889, p. 44.[/footnote]

One of his greatest contributions was as a mentor to area youth. According Edward W. Blyden, who visited in 1889, two Kpelle youth trained by Hill had “their own coffee farms and live in neat frame houses, cultivating from thirty to fifty acres of land. One of them has recently married a highly esteemed colonist, widow of one of the late prominent settlers.” [footnote]”Visit to Arthington, African Repository, April 1889, p. 44.[/footnote]

A New Era reporter noted that Rev. Moore seemed to be competing with Hill, his neighbor and business partner, in planting coffee and foodstuff. In 1873, Moore had 700 coffee trees and a large coffee nursery. He was also self-sufficient in potatoes, cassava and eddoes. [footnote]”Arthington, Liberia,” African Repository, Nov. 1873, p. 337.[/footnote]

Moore reportedly received most of his religious training in Liberia. He told a visitor he knew “nothing of religion in America. He belonged to a Presbyterian family, but he had no religious impressions till he came to Africa. Here he became converted, joined the Baptist church, entered the ministry, and has recently been elected pastor of the church.” [footnote]”Visit to Arthington, African Repository, April 1889, p. 44.[/footnote]

In 1889, the church was planning to build a larger sanctuary. The original building was now too small for the congregation, many of whom were Indigenous Africans.[footnote]”Visit to Arthington, African Repository, April 1889, p. 44.[/footnote]

By the early 1880s Arthington was the site of the AME Mount Carmel Church, the Lutheran Muhlenberg Mission school and a Baptist church that included 66 “native” congregants, with native students in the schools. [footnote]Liberia Bulletin, 4, pp. 13-16; Cassell 1970, pp. 281, 284, 313, 322, 341, 343, 379.[/footnote]

In 1883, the local Union League Society was incorporated, naming George Askie, S.R. Hoggard, Solomon York, James H. Rawlhac, McGilbert Lawrence, W. L. Askie, S.W. Askie, Robert Mitchell and W. L. Carter]. [footnote] Acts of the Liberian Legislature, 1883, p. 19.[/footnote]

Four years later, the national legislature gave seventy five acres of land for the Anna Morris School of Arthington, with Edward S. Morris as sole trustee. [footnote] Acts of the Liberian Legislature, 1887, p. 3.[/footnote]

In 1888 it was estimated that Arthington alone was producing large quantities of ginger and other produce for local markets, along with 100,000 pounds of coffee for export, 10 percent of which was by Hill and Moore. [footnote]C. A. Cassell. (1970). Liberia. New York: Fountainhead, p. 242, 244, 263, 343; T. W. Shick. (1980). Behold the Promised Land. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 75, Table 17, p. 108; M. B. Akpan (1973). “Black Imperialism.” The Canadian Journal of African Studies, pp. 217-236; African Repository, 34 (1858), pp. 68-70; A. B. Williams. (1878). The Liberian Exodus. Charleston, South Carolina: The News and Courier Book Presses, p. 47.[/footnote]

Also that year, Arthington and neighboring Clay Ashland were in the grips of an enthusiastic temperance movement that resulted in a law banning the sale of liquor in the two towns, both major producers of sugar cane.[footnote] TWP, 1969, p. 28; Cassell, 1970, pp. 189, 216, 264, 341, 344.[/footnote]

Arthington and other St. Paul’s River towns benefited from the technical innovations of the local Muhlenburg Mission, a vocational school led by Rev. John Day. When Edward W. Blyden visited in 1889, the school’s large workshop was being conducted by Clement Irons, who emigrated in 1878 from Charleston, South Carolina. [footnote]”Visit to Arthington, African Repository, April 1889, p. 44.[/footnote]

Blyden noted, “they build arts and wheelbarrows, run steam engines, make farming implements, &c. Mr. Irons has constructed a steamboat for the river of native timber. It was launched from the mission a few weeks ago by the pupils only — 75 of them took hold of it and pushed it from the mission hill down into the water.” He called the school “a model for missions in this country.” [footnote]”Visit to Arthington, African Repository, April 1889, p. 44.[/footnote]

In 1893, a fifth regiment was added to the national militia, with troops to be drawn from Arthington, along with Clay-Ashland, Louisianna, Millsburg, Harrisburg, Muhlenburg, White Plains, Robertsville, Crozerville, Bensonville and Careysburg. [footnote] Acts of the Liberian Legislature, 1893, p. 6.[/footnote]

When the Saint Paul’s Baptist Church was incorporated in 1896, Rev. June Moore was pastor with deacons J.C. Taylor, Solomon Hill, E. Ponder, V.L. Miller, Henry Taylor and George Askie. [footnote]Acts of the Liberian Legislature, Acts 1896, p. 37.[/footnote]

At the time of his death on Dec. 25, 1898, Rev. June Moore was president of the Liberia Baptist Convention, which he and other successful farmers and traders had contributed significantly to making self-sufficient. [footnote]C. A. Cassell. (1970). Liberia. New York: Fountainhead, p. 242, 244, 263, 343; T. W. Shick. (1980). Behold the Promised Land. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 75, Table 17, p. 108; M. B. Akpan (1973). “Black Imperialism.” The Canadian Journal of African Studies, pp. 217-236; African Repository, 34 (1858), pp. 68-70; A. B. Williams. (1878). The Liberian Exodus. Charleston, South Carolina: The News and Courier Book Presses, p. 47.[/footnote]

In the 1905 elections, the TWP nominees for Montserrado were R. H. Jackson for the senate and C. R. Branch of Arthington, Henry Moses Ricks of Clay-Ashland, C. C. Porte of Crozierville and A. B. Mars of Paynesville for the House. The Dissatisfied Whigs, aligned with Coleman, endorsed R. H. Jackson, but put forward the names of J. B. Dennis of Monrovia, W. B. Gant of Brewerville, Z. N. Brown of New Georgia and George Dixon of Sasstown. [footnote]African Agricultural World, February 1905; African Agricultural World, March 1905.[/footnote]

In the early 1900s, as brass bands and fraternal lodges were proliferating in many coastal communities, Arthington was not to be left out. In 1916, the local Number One Brass Band was formed, with John Moore, band director; Johnny Bracewell, band master; W. H. Tyler, band instructor; Scott Carter, band leader; James Hoggard, financial secretary; Emma Tyler, band treasurer; Solomon Miller, boatswain; Thomas H. Tyler, band patron; and members: Joseph Bracewell and Jerry Jones. [footnote]Acts of the Liberian LegislatureActs 1916, p. 12.[/footnote]

That same year, the Coleman’s Memorial Lodge No. 134, United Brothers of Friendship of Arthington was incorporated, naming Thomas H. Tyler, p.m.; June Moore, p.m.; W. H. Tyler, w. m.; H. W. Davies, d. m.; Willie A. Moore, w. s.; Francis Hill, assistance secretary; James Clarke, chaplain; David Moore, marshall; trustees: John Moore and Henry Hill; W. H. Tyes, treasurer; Charles R. Askie, pilot; and Lot Hill. [footnote] Acts of the Liberian Legislature, Acts 1916, p. 13.[/footnote]

The Saint Paul’s Baptist Church was reorganized in 1917-18, with Rev. R. B. Wicker, pastor; J. C. Taylor, sen.; Solomon Hill, sen.; George Askie, church clerk; Thomas H. Tyler, building treasurer; and deacons: George Askie, Eli Poner, Henry Tylor, E. Samuel Moore and Menford F. Smallwood. [footnote]Acts of the Liberian Legislature, Acts 1917-18, p. 37.[/footnote]

In 1935, the Queen Esther Household of Ruth No. 5743 of the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows was formed. Listed as officers were L. N. B. Tyler, past most noble governor; Rebecca Bracewell, most noble governor; Mary Lawrence, right noble governor; L. A. Hill, recorder; G. B. Groove, noble governor and chamberlain; L. B. Turbett, shepherd and usher; W. H. Tyler, treasurer; H. M. Moore, worthy counsel; Hattie Brisbane, right senior steward; and trustees A. E. Diggs, A. E. Gall and P. J. Bracewell. [footnote] Acts of the Liberian Legislature, Acts 1935, pp. 38-39.[/footnote]

Two years later, the legislature approved the “Pride of Arthington Temple” No. 137, Sisters of the Mysterious Ten, naming Beatrice A. Tyler, worthy princess; Salomi Moore, worthy vice princess; Lillian Hill, secretary; L. B. Tucker, assitant secretary; W. H. Tyler, worthy treasurer; Lilly Mason, chaplain; Penelope Moore, zilla; Viola Tyes, marshal; Hannah Moore, senior marshal; trustees: June Moore, Willie Moore, Reginald L. Brown, Daniel B. Warner, Major M. Branch; sick committee: Julia A. Warner, Margaret Grove, Cordelia Moore, Lecretia Raynes and Nora Cooper; and members: Louise Mars, Elfreda Witherspoon, Mattie Branch, Harriet Trinity, Beatrice Moore, Eugenia Turkle and Dianah Obey. [footnote] Acts of the Liberian Legislature, Acts 1937, pp. 92-93.[/footnote]

In 1938, Attorney General Louis A. Grimes in an arbitration ordered that the sum of $181.60 be paid to resident Charles Vanah Wright as compensation for use by the government of his house and entire premises as a “pest house” in 1929 for housing small pox cases. [footnote] Acts of the Liberian Legislature, Acts 1938, p. 64.[/footnote]

Acts Tag Cloud

[do_widget id=categorizedtagcloudwidget-2]

Bensonville Map

Blog Post Title

What goes into a blog post? Helpful, industry-specific content that: 1) gives readers a useful takeaway, and 2) shows you’re an industry expert.

Use your company’s blog posts to opine on current industry topics, humanize your company, and show how your products and services can help people.

In Defense of J. J. Roberts

March 15th was the birthday of one of the greatest men that ever lived. As happens every year, the day went largely unnoticed by those who today feast on the fruits he planted.

That man was Joseph Jenkins Roberts, who labored to lay deep the foundation of Liberia. Yes, he was the country’s first president, but that was only one among many significant achievements.

Less known but equally noteworthy, he won quick recognition of Liberia’s independence from both Britain and France, the two superpowers at the time. This was no small feat for a former slave leading a “nation” of a few thousand citizens.

What is even more significant, he did it when those two rivals were constantly at each other’s throats. Imagine a tiny nation in the 1950s winning the backing of both the United States and the Soviet Union!

Another one of his huge contributions is hardly ever noted: He left office when his term was up! In so doing, he set a precedent that would stick for 100 years.

The first major break in that pattern came when the late William V. S. Tubman remained in the presidency for 27 years. After his death came the deluge.

After leaving the presidency, Robert went on to found and lead Liberia College, one of the first modern institutions of higher education in Africa. Upon his death, he left a significant portion of his estate to the Methodist Church for “the education of Liberia’s youth.” That largess helped fund the elementary school in Monrovia that bears his name. It is also a source of scholarships till this day.

Roberts left behind thousands of letters, documents and speeches. Most are preserved in the Liberian National Archives, the U. S. Library of Congress and other such facilities. Yet, no one has ever written a book about him for adult readers. His papers have never been published.

Liberia is probably the only country in the world without a biography of its founding president. The flaws of Senghor of Senegal, Toure of Guinea, Nrumah of Ghana and countless others have not kept people from publish their papers and writing biographies.

The fact that George Washington owned slaves and engaged in land speculation has not stopped Americans from honoring him either. So, what did Roberts do to deserve such shabby treatment?

Roberts’s rich and honorable legacy remains buried beneath a heap of “ma cussing” masquerading as scholarship. It started with Edward Wilmot Blyden, who claimed Roberts was the head of a mulatto cabal that suppressed dark-skinned repatriates (1).

Without a doubt, Blyden is and should forever remain an important historical figure, not just in Liberia but in the larger pan-African context (2). He was a prolific writer as well as, in my view, “an organic intellectual.” By that I mean someone who is the spokesman for a social group, whether or not that person has a bunch of academic degrees behind his name (3).

Having said all that, it is important to also note that Blyden had no training in sociology or the writing of history. He was primarily a polemicist, and his comment about Roberts heading a “mulatto cabal” must be viewed as such.

Why do I say that?

First, let’s begin with the context. Blyden made his claim during the election of 1869, which pitted the dark-skinned Edward James Roye against the light-complexioned James Spriggs Payne. This was a politically charged environment, with the ideologues of newly minted True Whig Party slinging whatever mud they could to advance the cause of their candidate.

Roye was very much like Donald Trump is today in the United States: an incredibly rich man with a deep feeling of entitlement who was willing to buy his way into office while destroying the society with inflammatory and divisive rhetoric.

Second, what was Blyden’s role in the election? He was not some neutral reporter or detached scholar, as some seem to imagine. He was THE chief polemicist of the True Whig Party, whose standard bearer was Edward James Roye. Knowing Blyden’s role as a party propagandist, contemporary scholars should all be skeptical about his claim.

In saying “be skeptical,” I am not saying we should dismiss Blyden. Instead, we should factor into the equation what is known about Blyden’s character and his truthfulness.

Many may find this hard to believe, but it was Roberts himself who helped to advance Blyden’s early career by appointing him editor of the Liberia Herald and, later, member of the Liberia College faculty (4).

Just one other tidbit about Blyden’s character will suffice. His “fall from grace” in Liberian society was not at the hands of Roberts and the so called light-skin cabal. It occurred during the tenure of Edward James Roye, the man he helped bring to the presidency.

Members of the True Whig Party dragged Blyden from the president’s home and almost lynched him for allegedly committing adultery with Roye’s wife. He was rescued from the mob by a group that included former president James Spriggs Payne, one of the politicians accused by Blyden of suppressing dark-skinned repatriates (5).

The adultery charge was buttressed by Rev. Alexander Crummell, a onetime Blyden ally who broke with him after the incident at Roye’s house (6).

We should also weigh Blyden’s disparagement of Roberts against available evidence. What evidence do we have?

We have several collections of letters written by early dark-skinnedLiberians that have been published, including Dear Master and Slaves No More (9). None of those diverse letter writers mentioned a “mulatto cabal” or described Roberts as oppressive of dark-skinned repatriates. On the contrary, the public often referred to him affectionately as J. J., much like Ghanians once called Flight Lt. Rawlings as “J. J.” too.

After leaving the presidency, Roberts served as the first head of Liberia College. He likely had a hand in selecting students during his tenure. Contrary to Blyden’s claim, many student from that period were dark-skinned, included A. B. King, T. W. Haynes, R. B. Richardson and Arthur Barclay, future president of Liberia (8).

In addition, the few images we have from early Liberia do not back Blyden claims. Two of Liberia’s four presidents before Roye were dark-complexioned, namely Stephen A. Benson and Daniel B. Warner (7). They all belonged to same political group as Roberts.

Those four presidents reflected the makeup of their constituents. Citizenship at the time was limited to a few settlements along the coast. Most of the early repatriates were free-born “people of color” from the Chesapeake – Delaware, Maryland, Virginia and North Carolina. In that region, about 50 percent of Africa-Americans were mixed race. In Virginia, they made up 65 percent of the black population (8).

If the evidence does not support Blyden’s claim, why is his disparagement of Roberts widely repeated today? Two factors come to mind.

First, most of our leading “scholars” see scholarship merely as a tool for achieving narrow political ends. Research, in their view, requires no verification or supporting evidence. It is a “so say one, so say all” proposition. If the big man says so, it must be true.

Instead of examining the writings of Roberts and others directly, they rely entirely on E-L-They-Say.

When they were leaders of opposition movements, they simply collected and repeated every criticism anyone had ever voiced against any Liberian government in any era. Since Blyden was critical of the government, they merely repeated what he said without asking if it was true.

Second, many of our leading “scholars” view the world through a dualistic lens. Either you’re for Blyden or you’re against him. And being “for him” means seeing him as a heavenly angel, without human frailties or flaws.

Their works are filled with characters portrayed in stark terms as black/white or good/evil, similar to what one finds in children’s fables or tv melodramas. They have contributed to superficiality of current Liberian discourse, with its focus of appearance and diction rather than the substance of ideas. How ironic for men who call themselves “intellectuals.”

Their simplistic and patently biased approach to research is one of the key factors blocking the advancement of Liberia.

Because they view scholarship as a political tool, their tune has changed radically in recent years. As the well-paid intellectual lights of the current administration, they have suddenly gone blind, deaf and dumb; they see no evil, hear no evil and dare not speak a critical word about current conditions.

If I am critical of the “scholars” who dominate the Liberian landscape today, I am not being critical for criticism sake. I offer this analysis in hope that younger scholars will break free so that Liberia finally gets a scholarship worthy of the name. In digging Joseph Jenkins Roberts out from beneath the dirt thrown over him, I pray that young Liberians will one day aspire to his example of philanthropy and servant-leadership, rather than the corrupt and selfish conduct of his contemporary critics.

For more information, see the following texts:

Edith Holden, Blyden of Liberia. New York: Vantage, 1966, p. 649.

Hollis R. Lynch, Edward Wilmot Blyden: Pan-Negro Patriot, 1832-1912. New York: Oxford University Press, 1970.

Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks. New York: International Publishers, 1973.

Holden, Blyden, 649; Lynch, Edward Wilmot Blyden, 15.

Carl Patrick Burrowes, Power and Press Freedom in Liberia. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2004, pp. 88, 104.

Wilson Jeremiah Moses, Alexander Crummell: A Study of Civilization and Discontent. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989, p. 192.

See attached images.

James Oliver Horton, Free People of Color. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993.

United States. Bureau of Education. Report of the Commissioner of Education Made to the Secretary of the Interior. Washington, DC: Bureau of Education, 1870.

Randall M. Miller. Dear Master: Letters of a Slave Family. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1990; Bell Irvin Wiley. Slaves No More: Letters from Liberia, 1833-1869. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

Author’s note: C. Patrick Burrowes, Ph. D.

Burrowes is the author of Between the Kola Forest and the Salty Sea: A History of the Liberian People Before 1800. The book, which took 30 years to research, will be published in a few months. To learn more about the book, go to Kickstarter.com and search for “Kola Forest.” For information on the author, visit www.patricksplace.org.

Published in the Daily Observer newspaper, March 17, 2016.

Poor Liberia! Few countries in the world have been as ill served by its government officials, as Liberia has been.

In the 1920s, Liberia earned the opprobrium of the world when some selfish officials opted to supply laborers by force to private foreign contractors. The cries and protests of ordinary Liberians went unheeded by them, until international pressure brought an end to their heartless scheme.

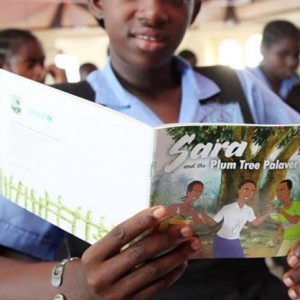

If this government is allowed to outsource the entire elementary school system, Liberia will enter the annals of infamy once again. At stake is not just the future of education in Liberia. If this proposal is allowed to pass, it will be the beginning of the end for universal public education, a concept with roots dating back to 1647. At stake is the future schooling of children around the world.

The proposal must be blocked, not just as a matter of principle. It must be opposed because it is based on faulty logic. Furthermore, its advocates provide no evidence to support their radical and disruptive experiment with the nation’s school system. Instead, they offer ideological buzzwords like “privatization” and “technology.”

But technologies cannot teach; people do. The top three factors for ensuring student success in early childhood education are: good teachers, good teachers, and good teachers. In other words, the quality of teaching and teacher-support are the strongest predictor of quality. If successful Liberians are humble and honest, we will readily acknowledge that we owe whatever careers we have today to the foundation laid by good elementary school teachers.

Throughout its history, Liberia produced thousands of such dedicated and self-sacrificing educators. The late Albert Porte and Dr. Mary Antoinette Brown-Sherman are just two well-known examples. Each of us could name several others who impacted our lives directly. Those teachers worked with few, if any, advanced technologies. Yet, their impact in the lives of students was immeasurable. So, why the urgent need now for the outsourcing of curriculum delivery and classroom management by cell phones?

The main reason is this: The Liberian educational system over the last decade has been driven by donors’ agendas, with little systematic planning based on local needs. Donors love giving chairs, buildings and other concrete objects that they can slap their logos on for all to see. It is fine to accept those inputs, but government should have its own master plan. The plan should determine allocation of resources, not the other way around.

Two years ago, President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf famously characterized the educational system as “a mess.” That was an indirect admission of systematic failure due to lack of planning. But instead of fixing the underlying problem, a new Education Minister – with less competence than the previous one – was brought on board.

Regardless of who is at the helm, the education ministry has been unable to generate a plan. Having failed to fulfill its mandate, we are now seeing the ministry simply offering to pass off its core functions to others who are even less answerable to the public.

The ministry’s current proposal offers to throw two “magic potions” at our systemic educational problems: privatization and delivery of curriculum via cellphones. Privatization in particular has been pushed as a cure-all for educational problems mainly by Republicans in the United States. In contrast, the best elementary school systems in the world, such as Norway and Singapore, have not embraced privatization.

Even in the U. S., no state has ever privatized its entire elementary school system, not even states run by Republican governors and legislature. Instead, a limited number of charter schools have been allowed to compete with public schools on an experimental basis. The results so far are mixed: some charter schools have performed well, but many have failed abjectly.

Ditto with technology as a panacea in elementary schools. That idea has been enthusiastically embraced by the U. S., but not by the world’s top school systems. Even in the U. S., technology is only widely adopted after careful experiments are done. And only after teachers receive technology training.

U. S. enthusiasm for computers in schools is not surprising. American manufacturers have a long history of overselling new and unproven technology to schools, without delivering promised results. As unbelievable as it might seem, television sets were once promoted as replacement for teachers, much as some people were doing with computers recently. Even computers are losing their luster. Some school districts that spent millions to stock classrooms with iPads are now taking them out.

Worst of all, the solutions being advocated by the education ministry are not home-grown options. As with most of the policies implemented in Liberia over the past decade, they are part of a neo-liberal framework that is being pushed by the World Bank and other international actors. The World Bank has been wrong before, as it is wrong on this issue. While those “foreign partners” may have compelling justifications for their recommendations, it is the responsibility of government officials to present the legislature with thoroughly vetted options.

What alternative policies were considered and, if so, why were they rejected? Did the Ministry of Education consult with the education faculties at Cuttington University or the government’s own University of Liberia or even with administrators and teachers at successful private and faith-based schools? Was any effort made to get input from highly qualified Liberian teachers and school administrators in the Diaspora? Why did the government of Liberia disregard its own Vision 2030, its roadmap to middle-income status, which contained no plan for outsourcing education?

If privatization and cellphone delivery of curriculum are adopted by Liberia, they will not be free. Liberian taxpayers will foot the bill for this expensive boondoggle. Further, future generations will suffer for the resulting deficit in their education. In addition, Liberia will suffer another shameful international scandal.

The shame will rest, not only on Bridge Academies and its local agents, but on all Liberians who watched silently from the side-lines as the country’s future was sold for thirty pieces of silver. Will all the graduates of the Zorzor Teachers Training Institute and the Kakata Teachers Training Institute turn a blind-eye to this decimation of the educational system? What about the illustrious relatives and professed acolytes of Albert Porte, a life-long school teacher? As African nationalism is being strangled to death in the land of its birth, where are all the self-proclaimed followers of Edward Wilmot Blyden, including the head of the so-called “Good” Governance Commission, Dr. Amos C. Sawyer? Will the generations of students nurtured and protected by Mary Antoinette Brown-Sherman remain silent as her legacy is betrayed? Where do presidential candidates and opposition leaders stand on this crucial issue?

Working together, Liberians at home and in the Diaspora can defeat this shameful sellout of our patrimony. To avoid the chaos that could come from a mass protest march, I suggest we inundate the government with 10,000 letters of protest. That would be a fittingly educated form of protest. The emblematic protest-moment would be when a delegation delivers wheelbarrows filled with letters to the government.

Some people view protest as useless because our officials are deaf to the cries and concerns of the public they have sworn to serve. Nonetheless, the public should still register its disapproval. Our officials must be shown that Liberians are not sheep. For precedence we need look no further than the late Albert Porte, many of whose essays were directed against policies that were already adopted.

I know many of our officials could care less about Liberians have to say, but if we mobilize world public opinion against their plan, they will listen. I know from experience: When Ellen Johnson Sirleaf and others were imprisoned in the 1980s; some of us mobilized international pressure that resulted in their release.

Many education scholars and activists around the world have already condemned this nefarious plan. International media will no doubt respond both to the symbolism of our dissent and the substantive issues we are raising. In the end, “foreign partners who prefer backroom deals see foreign partner who work in broad daylight, foreign backroom partner will jek.”

Moments arise in history that tests the honor and moral fiber of a people. The forced-labor scandal of the 1920s was one. This educational outsourcing boondoggle is another. By our actions, let us prove ourselves worthy of the respect we want from the rest of the world and from our descendants.

Author’s Note: C. Patrick Burrowes, Ph. D.

Burrowes is the author of Between the Kola Forest and the Salty Sea: A History of the Liberian People Before 1800. The book, which took 30 years to research, will be published in a few months. For information on the author, visit www.patricksplace.org

Published in FrontPage Africa newspaper, April 7, 2016

About 2

[title type=”h3″ class=””]Giving Voice to the Voiceless[/title]

(Continued from “About” page)

My journalism career was “derailed” when I took a graduate seminar with a passionate historian, Cathy Covert, who taught me the value of “history from the bottom up.” To be simplistic, writing history shares with investigative reporting a focus on using multiple sources to answer big questions of “why” and “how” in a dispassionate way. But where reporting draws upon mainly live sources to address current problems, history uses the records of dead people to investigate the past.

While earning a master’s degree, I worked with Laubach Literacy International, where I was reminded daily of the hardships faced by people who cannot read or write. In addition, my male-chauvinist assumptions and behaviors were being challenged by several female friends; through them I was introduced to history written from women’s perspective. Together, these experiences deepened my commitment to documenting the stories of people who are traditionally ignored, marginalized and overlooked.

My specific interest in the history of Liberians took an academic turn in the late 1970s, when I encountered the writings of Dr. Mary Antoinette Brown-Sherman. A devotee of Blyden, she encouraged Liberian scholars to build upon local traditions.

In my view, Dr. Brown-Sherman was the greatest Liberian scholar of the late twentieth century. Her work on the role of the Poro Society in education inspired my research on African spirituality or “the way of the ancestors.” Regrettably, a lot of Liberians pay lip-service to her legacy but fail to heed her admonitions or to build upon her approach.

While in college, I also “discovered” the writings of Dr. Walter A. Rodney, whose best known work is How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. From Rodney I learned that history is made as much by those who till the rice fields as by merchants and monarchs. His History of the Upper Guinea Coast: 1545-1800 is the most important history of the Mano River Region published in the last 50 years. But many scholars in Liberian studies shun Rodney’s works because he did not share their worldview.

Most of my research and scholarship activities relate to investigating history, as well as the intersection of ideology and power in communication.

I write free-verse poetry (most of which remains unpublished), and I occasionally publish commentaries in the media. But, mostly I write history – Liberian history and media history. To be more precise, you could describe my work as deeply researched historical nonfiction. I co-authored the current edition of the Historical Dictionary of Liberia and published a book on government-press relations in Liberia from 1830 to 1970. The rest of my writings have appeared mainly in peer-reviewed scholarly journals.

I write free-verse poetry (most of which remains unpublished), and I occasionally publish commentaries in the media. But, mostly I write history – Liberian history and media history. To be more precise, you could describe my work as deeply researched historical nonfiction. I co-authored the current edition of the Historical Dictionary of Liberia and published a book on government-press relations in Liberia from 1830 to 1970. The rest of my writings have appeared mainly in peer-reviewed scholarly journals.

As a life-long university professor and administrator, I’ve been paid to do what I love – read, build knowledge and challenge young adults to excel. A few disappointments and regrets aside, my life has been golden.