March 15th was the birthday of one of the greatest men that ever lived. As happens every year, the day went largely unnoticed by those who today feast on the fruits he planted.

That man was Joseph Jenkins Roberts, who labored to lay deep the foundation of Liberia. Yes, he was the country’s first president, but that was only one among many significant achievements.

Less known but equally noteworthy, he won quick recognition of Liberia’s independence from both Britain and France, the two superpowers at the time. This was no small feat for a former slave leading a “nation” of a few thousand citizens.

What is even more significant, he did it when those two rivals were constantly at each other’s throats. Imagine a tiny nation in the 1950s winning the backing of both the United States and the Soviet Union!

Another one of his huge contributions is hardly ever noted: He left office when his term was up! In so doing, he set a precedent that would stick for 100 years.

The first major break in that pattern came when the late William V. S. Tubman remained in the presidency for 27 years. After his death came the deluge.

After leaving the presidency, Robert went on to found and lead Liberia College, one of the first modern institutions of higher education in Africa. Upon his death, he left a significant portion of his estate to the Methodist Church for “the education of Liberia’s youth.” That largess helped fund the elementary school in Monrovia that bears his name. It is also a source of scholarships till this day.

Roberts left behind thousands of letters, documents and speeches. Most are preserved in the Liberian National Archives, the U. S. Library of Congress and other such facilities. Yet, no one has ever written a book about him for adult readers. His papers have never been published.

Liberia is probably the only country in the world without a biography of its founding president. The flaws of Senghor of Senegal, Toure of Guinea, Nrumah of Ghana and countless others have not kept people from publish their papers and writing biographies.

The fact that George Washington owned slaves and engaged in land speculation has not stopped Americans from honoring him either. So, what did Roberts do to deserve such shabby treatment?

Roberts’s rich and honorable legacy remains buried beneath a heap of “ma cussing” masquerading as scholarship. It started with Edward Wilmot Blyden, who claimed Roberts was the head of a mulatto cabal that suppressed dark-skinned repatriates (1).

Without a doubt, Blyden is and should forever remain an important historical figure, not just in Liberia but in the larger pan-African context (2). He was a prolific writer as well as, in my view, “an organic intellectual.” By that I mean someone who is the spokesman for a social group, whether or not that person has a bunch of academic degrees behind his name (3).

Having said all that, it is important to also note that Blyden had no training in sociology or the writing of history. He was primarily a polemicist, and his comment about Roberts heading a “mulatto cabal” must be viewed as such.

Why do I say that?

First, let’s begin with the context. Blyden made his claim during the election of 1869, which pitted the dark-skinned Edward James Roye against the light-complexioned James Spriggs Payne. This was a politically charged environment, with the ideologues of newly minted True Whig Party slinging whatever mud they could to advance the cause of their candidate.

Roye was very much like Donald Trump is today in the United States: an incredibly rich man with a deep feeling of entitlement who was willing to buy his way into office while destroying the society with inflammatory and divisive rhetoric.

Second, what was Blyden’s role in the election? He was not some neutral reporter or detached scholar, as some seem to imagine. He was THE chief polemicist of the True Whig Party, whose standard bearer was Edward James Roye. Knowing Blyden’s role as a party propagandist, contemporary scholars should all be skeptical about his claim.

In saying “be skeptical,” I am not saying we should dismiss Blyden. Instead, we should factor into the equation what is known about Blyden’s character and his truthfulness.

Many may find this hard to believe, but it was Roberts himself who helped to advance Blyden’s early career by appointing him editor of the Liberia Herald and, later, member of the Liberia College faculty (4).

Just one other tidbit about Blyden’s character will suffice. His “fall from grace” in Liberian society was not at the hands of Roberts and the so called light-skin cabal. It occurred during the tenure of Edward James Roye, the man he helped bring to the presidency.

Members of the True Whig Party dragged Blyden from the president’s home and almost lynched him for allegedly committing adultery with Roye’s wife. He was rescued from the mob by a group that included former president James Spriggs Payne, one of the politicians accused by Blyden of suppressing dark-skinned repatriates (5).

The adultery charge was buttressed by Rev. Alexander Crummell, a onetime Blyden ally who broke with him after the incident at Roye’s house (6).

We should also weigh Blyden’s disparagement of Roberts against available evidence. What evidence do we have?

We have several collections of letters written by early dark-skinnedLiberians that have been published, including Dear Master and Slaves No More (9). None of those diverse letter writers mentioned a “mulatto cabal” or described Roberts as oppressive of dark-skinned repatriates. On the contrary, the public often referred to him affectionately as J. J., much like Ghanians once called Flight Lt. Rawlings as “J. J.” too.

After leaving the presidency, Roberts served as the first head of Liberia College. He likely had a hand in selecting students during his tenure. Contrary to Blyden’s claim, many student from that period were dark-skinned, included A. B. King, T. W. Haynes, R. B. Richardson and Arthur Barclay, future president of Liberia (8).

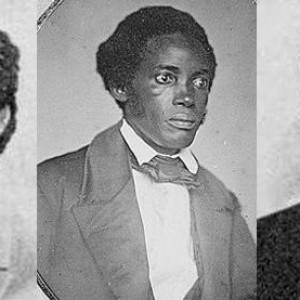

In addition, the few images we have from early Liberia do not back Blyden claims. Two of Liberia’s four presidents before Roye were dark-complexioned, namely Stephen A. Benson and Daniel B. Warner (7). They all belonged to same political group as Roberts.

Those four presidents reflected the makeup of their constituents. Citizenship at the time was limited to a few settlements along the coast. Most of the early repatriates were free-born “people of color” from the Chesapeake – Delaware, Maryland, Virginia and North Carolina. In that region, about 50 percent of Africa-Americans were mixed race. In Virginia, they made up 65 percent of the black population (8).

If the evidence does not support Blyden’s claim, why is his disparagement of Roberts widely repeated today? Two factors come to mind.

First, most of our leading “scholars” see scholarship merely as a tool for achieving narrow political ends. Research, in their view, requires no verification or supporting evidence. It is a “so say one, so say all” proposition. If the big man says so, it must be true.

Instead of examining the writings of Roberts and others directly, they rely entirely on E-L-They-Say.

When they were leaders of opposition movements, they simply collected and repeated every criticism anyone had ever voiced against any Liberian government in any era. Since Blyden was critical of the government, they merely repeated what he said without asking if it was true.

Second, many of our leading “scholars” view the world through a dualistic lens. Either you’re for Blyden or you’re against him. And being “for him” means seeing him as a heavenly angel, without human frailties or flaws.

Their works are filled with characters portrayed in stark terms as black/white or good/evil, similar to what one finds in children’s fables or tv melodramas. They have contributed to superficiality of current Liberian discourse, with its focus of appearance and diction rather than the substance of ideas. How ironic for men who call themselves “intellectuals.”

Their simplistic and patently biased approach to research is one of the key factors blocking the advancement of Liberia.

Because they view scholarship as a political tool, their tune has changed radically in recent years. As the well-paid intellectual lights of the current administration, they have suddenly gone blind, deaf and dumb; they see no evil, hear no evil and dare not speak a critical word about current conditions.

If I am critical of the “scholars” who dominate the Liberian landscape today, I am not being critical for criticism sake. I offer this analysis in hope that younger scholars will break free so that Liberia finally gets a scholarship worthy of the name. In digging Joseph Jenkins Roberts out from beneath the dirt thrown over him, I pray that young Liberians will one day aspire to his example of philanthropy and servant-leadership, rather than the corrupt and selfish conduct of his contemporary critics.

For more information, see the following texts:

Edith Holden, Blyden of Liberia. New York: Vantage, 1966, p. 649.

Hollis R. Lynch, Edward Wilmot Blyden: Pan-Negro Patriot, 1832-1912. New York: Oxford University Press, 1970.

Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks. New York: International Publishers, 1973.

Holden, Blyden, 649; Lynch, Edward Wilmot Blyden, 15.

Carl Patrick Burrowes, Power and Press Freedom in Liberia. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2004, pp. 88, 104.

Wilson Jeremiah Moses, Alexander Crummell: A Study of Civilization and Discontent. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989, p. 192.

See attached images.

James Oliver Horton, Free People of Color. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993.

United States. Bureau of Education. Report of the Commissioner of Education Made to the Secretary of the Interior. Washington, DC: Bureau of Education, 1870.

Randall M. Miller. Dear Master: Letters of a Slave Family. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1990; Bell Irvin Wiley. Slaves No More: Letters from Liberia, 1833-1869. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

Author’s note: C. Patrick Burrowes, Ph. D.

Burrowes is the author of Between the Kola Forest and the Salty Sea: A History of the Liberian People Before 1800. The book, which took 30 years to research, will be published in a few months. To learn more about the book, go to Kickstarter.com and search for “Kola Forest.” For information on the author, visit www.patricksplace.org.

Published in the Daily Observer newspaper, March 17, 2016.