Ray Cavanaugh, Retropolis, the Washington Post, November 20, 2021

The handwritten agreement details the sale of West African land that later became Monrovia, the country’s capital

It was billed as a land of promise — a place where free Black Americans could obtain more political rights and a better quality of life.

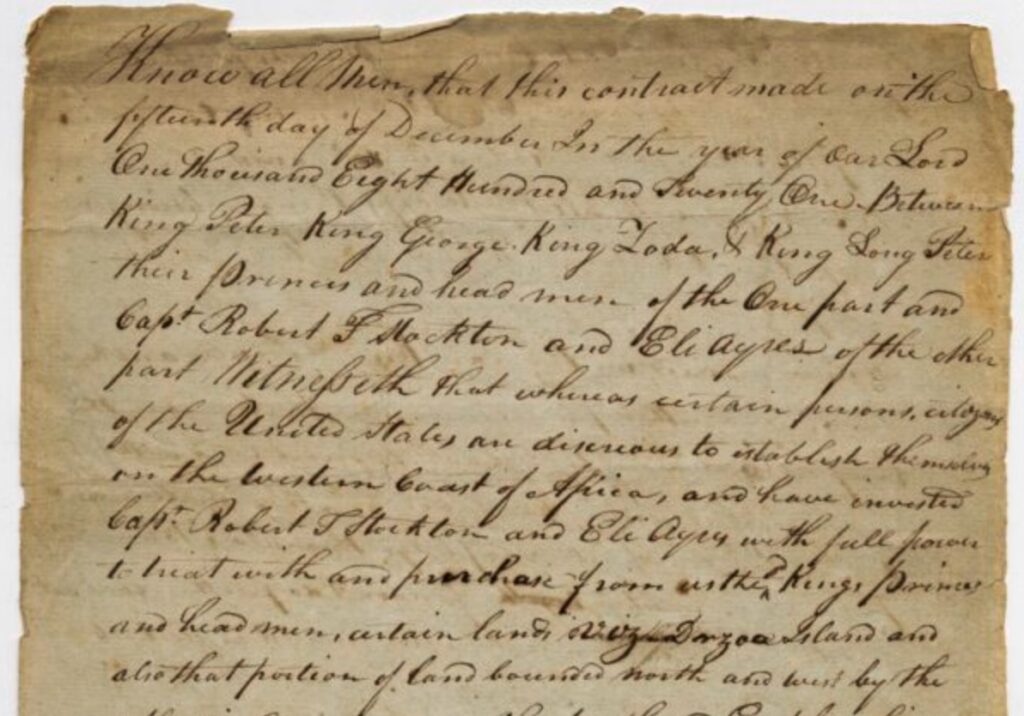

Liberia did not receive its name until 1824, but the territory that became its capital city was purchased on Dec. 15, 1821.

Almost exactly 200 years later, a Liberian historian has discovered that original purchase agreement — a document missing since 1835 that sheds light on the acquisition of the only U.S. colony in Africa.

C. Patrick Burrowes, who was born in Liberia and has taught at Penn State Harrisburg and Marshall University, uncovered the handwritten document in August. It details the sale of a tract of West African land that later became Monrovia, the Liberian capital. The selling price was about $300 worth of weapons, rum and other merchandise.

The document’s whereabouts had been unknown for so long, Burrowes said, that there was speculation it had never existed at all. For the historian, finding the purchase agreement has been the most significant discovery of his career, he said. And for historical understanding of Liberia’s origins, this document helps debunk several prevailing myths about the acquisition of territory that became its capital.

“The details of the land transfer have been shrouded in some controversy, so the recent discovery by Dr. Burrowes is timely, especially so close to the 200th anniversary of the event,” said Herbert Brewer, a Morgan State University historian who studies slavery and the African American diaspora.

Borrowing a phrase from President Biden, Brewer called the find a “BFD” that “will give historians and Liberians an opportunity to rethink the country’s history.”

No land surveys of the territory were conducted, so its precise dimensions went unspecified. Various sources would later provide hugely inflated numbers, but Burrowes deduced from an 1824 map that the initial purchase involved only about 140 acres. He added that a similar piece of land in much of the United States would have sold for considerably less in that era.

The buyers were two White men: U.S. naval Lt. Robert Stockton and Eli Ayres, an agent of the American Colonization Society (ACS), an organization founded in 1816 that sought to encourage and facilitate free African Americans to return to their ancestral continent.

Burrowes, who has spent several decades researching the ACS, said the text of the 1821 purchase agreement matched Ayres’s handwriting on other papers and that Stockton’s signature on the document matched his signature on other letters from the period.

The second page of the land contract, bearing the signatures of U.S. naval Lt. Robert Stockton and American Colonization Society agent Eli Ayres — the buyers — and local rulers Peter, George, Zoda, Long Peter, Governor and Jimmy. (Chicago History Museum)

Stockton, who would later attain the naval rank of commodore and become a U.S. senator for New Jersey, “embodied antebellum America’s contradictory stance on slavery,” Burrowes said. As one of the first officers on the

U.S. Navy’s anti-slavery patrol, Stockton was so dogged in pursuing foreign slave ships that he unsettled diplomatic relations with France, which filed a protest against one of his ship seizures. And yet for all his opposition to further importation of enslaved people, he had no objection to the South’s system of human bondage. In fact, he enslaved African laborers on his own Georgia sugar plantation.

Aside from Stockton’s convoluted relationship with slavery, much debate has persisted over the extent to which the ACS was truly an anti-slavery organization. Though the society did not pursue immediate abolition, it did rescue Africans from illegal slave ships and deliver them to Liberia.

The land purchase highlights the fact that opposition to slavery was not exclusive to clusters of outraged Americans. John Mill, a biracial West African native serving local rulers as a secretary at the purchase negotiations, had recently given up his lucrative slave-trade business because of a troubled conscience. The rulers were willing to listen to pro-slavery arguments, but they ultimately cast their lot with the opposing side by selling the land to the ACS, over the objections of local slave traders who saw the move as a threat to their business.

“One can say then,” Burrowes said, “that Liberia was founded as an abolitionist nation.”